Introduction

As horse owners we are becoming more aware that a great number of horse health and behaviour issues are related to what our horses eat. Healthy digestion is paramount to avoiding ulcers, colic and other problems. Horses possess a unique digestive system that differentiates them from ruminant animals like cows, which have a four-chambered stomach, including a rumen. Horses, as non-ruminant herbivores, have a single-chambered stomach, similar to humans, often referred to as the “simple stomach” or “monogastric” stomach. Their digestive anatomy makes them adept at efficiently digesting forage such as grasses and hay but less suited for processing concentrates or hard feed, which can include grains like oats, corn, and barley. This paper emphasizes the critical role of natural feeding in maintaining a horse’s digestive health and explores the implications of modern feeding practices on their well-being.

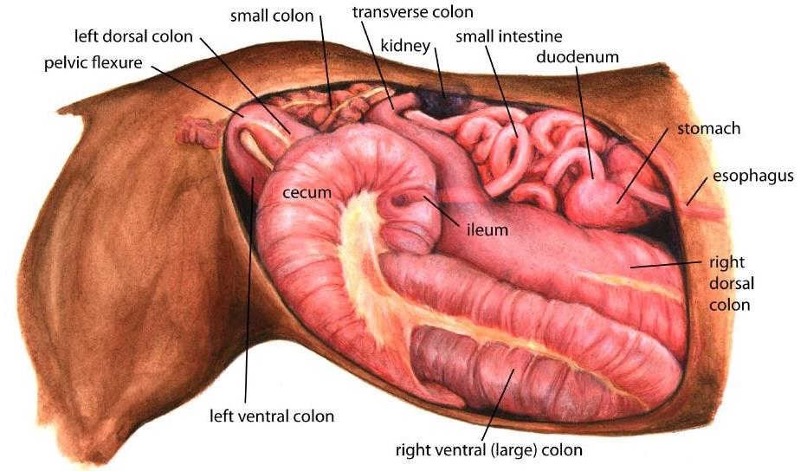

Fundamental Anatomy

Understanding the digestive system of the horse is fundamental to making sure that your horse has a healthy digestion.

The equine digestive system can be classified into two primary sections: the foregut and the hindgut. The foregut comprises the stomach and small intestine, while the hindgut, or large intestine, consists of the caecum and colon. In its entirety it is referred to as the Gastrointestinal (GI) tract

Mouth: Mastication, or chewing, is the first stage of digestion where feed is ground down to allow enzymes and bacteria to attack the cell walls of the horse’s plant-based diet.

Stomach: Remarkably, the equine stomach can only accommodate 2-3 gallons at a time, making it the smallest stomach relative to body size among all our domesticated animals. Depending on the size and content of the meal, such as hay versus grain versus liquids, food may reside in the stomach for as little as 15-30 minutes or as long as 12 hours, with an average of 3-4 hours.

Small Intestine: Moving down the digestive tract, we come to the small intestine, which stretches approximately 70 feet in length and comprises three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Food can traverse the entire small intestine in as little as 30-60 minutes but may take up to 8 hours.

Caecum: Continuing into the large intestine, the first stop is the caecum, a structure resembling a fermentation vat, akin to a cow’s rumen. This comma-shaped component on the horse’s right side is roughly 4 feet long and can hold 8 gallons.

Colon: The order of progression then moves to the large colon (10-12 feet long) and the small colon (also 10-12 feet long). The time taken for food to pass through the entire hindgut can range from less than a day to as many as 3 days.

The Equine Digestive Process

Given the distinct functions carried out in the front and back of the gastrointestinal tract, it is prudent to examine each part separately.

Foregut Digestion

Mouth

The physical action of chewing activates the three pairs of salivary glands in the horse’s mouth. This is the only time saliva is produced in horses. Saliva production in horses, just as in humans, is critical in helping the swallowing process and preventing choking. The more chewing, the more saliva that is produced.

Stomach

After horses gather, chew, and swallow their food, the stomach comes into play. The bicarbonate produced by the salivary glands protects the stomach from acid damage and contains small amounts of amylase which starts the breakdown of carbohydrates.

The upper 1/3 of the stomach, known as the “non-glandular region,” is where 80% of ulcers form. It relies on mucus and buffers from saliva to protect it. It lacks protection from stomach acid, unlike the lower, glandular section. The glandular region continuously produces hydrochloric acid which further breaks down food. Pepsinogen and stomach acids initiate the digestion and degradation of fats and proteins. The stomach mixes the food and regulates its passage via muscular contractions known as peristalsis. Essentially, the stomach acts as a holding and mixing tank, much like a cement truck continuously churning and blending ingredients.

Small Intestine

Most proteins, soluble carbohydrates and fats are broken down by digestive enzymes in the small intestine. The pancreas releases amylase into the small intestine for carbohydrate breakdown. Proteases continue the breakdown of proteins into amino acids. Bile from the liver helps emulsify fats into smaller globules. The nutrients are then absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal villi.

Healthy villi in the small intestine allow for maximum absorption of nutrients, but the tiny villi are sensitive to certain medications, parasites, and excess stomach acid. When cells in this area are damaged, the membrane barrier is compromised, allowing toxins and large molecules into the bloodstream (this is often referred to as ‘Leaky Gut’). This can result in body inflammation and suppressed immunity. Other health issues resulting from foregut issues include ulcers, laminitis, colic, GI tract inflammation and malabsorption of nutrients among other metabolic issues.

Hindgut Digestion

Fermentation in the hindgut enables most of the horse’s food digestion. What is being fermented is complex carbohydrates (fibre) into useful end products with the assistance of beneficial microorganisms. These microorganisms produce fatty acids, supplying energy and calories, as well as B-vitamins, Vitamin K, and some amino acids. The colon plays a dual role, absorbing these nutrients and a portion of the water accompanying food as it traverses the digestive tract.

Horse Digestive Problems

With such complexity in the equine digestive system, it’s unsurprising that issues occasionally arise. Nevertheless, the intricate nature of a horse’s digestive tract should not deter owners from maintaining a healthy system.

Gastric ulcers, characterized by erosions in the stomach lining, result from extended exposure to irritating acids on sensitive tissues. While short-term prescription medication may promote tissue healing, long-term management necessitates a combined approach involving pharmaceuticals, natural remedies, and dietary and lifestyle changes to preserve stomach health.

The PH and balance of microorganisms is critical to proper hind gut function. And that balance is easily disrupted. Situations that lower PH, creating an acidic environment or causing death to a portion of the microbiome can result in the release of endotoxins into the bloodstream potentially causing an array of issues including laminitis, founder, colic and leaky gut.

“Colic” is a general term denoting abdominal pain without specifying a cause or location in the horse’s belly. However, mitigating known risk factors, such as sudden changes in hay or grain, excessive grain consumption, abrupt shifts in activity, prolonged periods of stall confinement, inadequate parasite control, and restricted access to water, can significantly contribute to a smooth operation of the horse’s GI tract. On the other hand, prebiotics, enzymes, and yeast have shown their ability to support normal hindgut function.

The good health of the microbiome (bacteria and protozoa colonies) and having an adequate amount of water in the hindgut are two critical components to healthy equine digestion. Too little water intake can cause an excess of undigested material and result in impaction colic. Too much water remaining in the system can lead to diarrhoea.

Continual exposure to low PH can cause anorexia or malnutrition, colitis (inflammation of the colon) and other metabolic disorders.

Physical signs of hindgut issues may include a swollen caecum (right side in front of the hip), difficulty bending to the right under saddle, gut agitation and loose manure. If the caecum has an acidic environment, this can spill over into the large intestine causing damage, which can lead to diarrhoea, dehydration, poor absorption of nutrients, colic, ulcers and colitis.

The Role of Natural Feeding

Given these limitations in their digestive system, it’s crucial to carefully manage a horse’s diet to ensure their well-being. When feeding concentrates or hard feeds to horses, the following factors should be considered:

Gradual Introduction: If concentrates are a necessary part of the diet, they should be introduced slowly and in small amounts to allow the horse’s digestive system to adapt.

Balanced Diet: A horse’s diet should be balanced, with the appropriate ratio of forage to concentrates. The quality of forage should be a priority.

Monitoring and Management: Regularly monitor the horse’s body condition and adjust the diet as needed to maintain a healthy weight.

Avoid Overfeeding: Overfeeding concentrates, especially high-starch feeds, should be avoided to prevent digestive disturbances and health issues.

Importance of Stable Blood Sugar Levels

Natural feeding plays a pivotal role in maintaining stable blood sugar levels. Horses are grazing animals, exhibiting a lower tolerance for blood sugar instability compared to humans. Stable blood sugar levels in horses lead to natural digestion, balanced mood, stable energy, and healthy tissue rebuilding.

Modern feeding practices, with highly processed feeds, can disrupt stable blood sugar levels and contribute to various issues, including ulcers, excessive weight gain, decreased energy, skin problems, allergic reactions, and decreased muscle mass. Concentrated raw grain-based feeds, unnatural for horses, can lead to the fermentation of raw starch content in the hindgut, resulting in alcohol production and subsequent spikes in blood sugar.

Balanced Diet Components

A balanced horse diet should consist of the following components:

Forage: High-quality forage, such as good pasture or hay, forms the foundation of a horse’s diet. Forage provides fiber, energy, and essential nutrients. Horses should have access to forage throughout the day.

Concentrates: Concentrates, such as grains or pelleted feeds, can be added to the diet for horses with higher energy requirements. These should be chosen based on the horse’s activity level, age, and specific needs.

Protein: Horses require a balance of essential amino acids for muscle development, coat health, and more.

Vitamins and Minerals: Forage may not always provide all necessary vitamins and minerals. The specific needs depend on the horse’s age, activity, and the forage quality.

Water: Adequate clean, fresh water is essential for digestion, temperature regulation, and overall health. Horses can consume a significant amount of water daily, so access to water is crucial.

Electrolytes: Horses that sweat heavily may need electrolyte supplements to replace lost minerals. These supplements are often used during hot weather or strenuous exercise.

Fat: Adding fat to the diet can increase energy content without increasing the risk of colic associated with large grain meals.

Salt: Providing access to plain white salt (sodium chloride) allows horses to regulate their sodium intake according to their needs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, understanding the unique digestive system of horses and the implications of modern feeding practices is essential for promoting their overall well-being. Natural feeding, with a focus on high-quality forage and minimal starch and sugars, is vital in maintaining their digestive health. Stable blood sugar levels are crucial for horses, and natural feeding helps achieve this stability, ensuring balanced digestion, mood, and energy, while reducing the risk of various health issues associated with unstable blood sugar levels. Careful diet management, gradual introduction of concentrates, and regular monitoring of a horse’s body condition are fundamental steps in ensuring their health and longevity.